Colin Ross, "Unser Amerika" Chapter 3

3.

The German History of America

"Our America" - that sounds strange in the mouth of a German. We have become accustomed to seeing in America a daughter state of Great Britain. Even today I read the treatise of a well-known German politician and geographer who wrote of England and the United States of America as the two Anglo-Saxon states. At the same time, I heard a German who is about to become an American citizen passionately defend the character of America as an Anglo-Saxon country.

The Anglo-Saxon character of the United States is the most compelling example of the shaping power of a consistently championed idea. The power of the influence emanating from it is so strong that not only the German immigrants but even the majority of German visitors succumb to it, if they do not fall into the complete opposite and see in the German Americans a colony of the German national community and consequently make demands on them which only weaken the position of German Americanism and drive it even more over into the Anglo-Saxon camp.

In order not to fall into this mistake and in order not to see America too strongly through German glasses, I consciously kept away from the German-Americans during the first year of my last stay in America. I tried, and succeeded, in gaining a foothold in purely Anglo families and circles. The result was that I recognized German America from Anglo-Saxon, that I grasped that the essence of America is not to be Anglo-Saxon, but American, that is, a mixture of all the peoples of Europe on new soil. This mixture, however, is not yet of blood, but only of thought. That is why one cannot speak in any way of an American people, but only of an American state.

The struggle for the face of America has so far been waged mainly with ideas. And because the Germans in the New World lacked an idea of only approximately the same strength as the Puritan Anglo-Saxon democratic one, yes, because they lacked a unified igniting idea at all, that is why the German blood in the body of the people of the United States, despite its mass, did not come to bear.

Thus America has become Anglo-Saxon, in the imagination of the world as well as in our own. The political, linguistic and cultural sidelining of the German element was promoted by the fact that the share of the Germans in the construction of America was systematically reduced, yes, concealed, as in general the importance of the German nationality and German spirit in the world. I have in front of me a book intended for young people. "It is called "Heroes of World History”. I took it from the bookshelf of a German-American child. In this book, among all the heroes of the sword, the pen and the lyre, all the great figures of world history, world religions and world poetry, there is not a single German. Charlemagne is listed, but not as a German, but as a Frenchman. Among all the heroes of American history, who, as is to be expected in an American book, make up more than a good half, there is not a single one of German descent. Among the heroes of the War of Independence, Lafayette is probably listed, but not Steuben.

But can we blame the Anglo-Americans? When I went to school in Germany, I heard a lot about Lafayette on the occasion of the American Revolution, but not a word about Steuben, the Frederician general who first made an army out of the freedmen and bushwhackers. I am afraid my history teacher had never heard of him himself.

The case of Steuben shows what the account of the past means for the shaping of the future. Steuben was, in a sense, rediscovered by the German Americans only after the World War. The historical weight attached to it significantly strengthened their political position. But in the end it is not so much a matter of redressing Anglo-American historical representations and falsifications of history - as important as that is - it is more significant to grasp the nature and significance of the ethnic Germans in America from one point of view as a unified idea. Until this is accomplished, Germans in the United States will remain what they have always been, "also-Americans" at best. They also fought in the War of Independence and the War of Secession, they also helped to open up the West, they also helped to build the great and powerful United States.

But all this does not help much. It does not bring together the Germans who are scattered all over the country and who are scattered in innumerable parties, coteries, associations and groups. It does not bring them to the fore and not to leadership. Only an idea that grasps them equally as Americans and as Germans, that does not at best tolerate their German nature as not detrimental to the American nature, but that on the contrary makes their German blood, their German heritage the very precondition of their Americanism, that fills them with the unshakable conviction that they can only be good Americans if they are good Germans.

Such an idea cannot be artificially created, it cannot be intellectually conceived. It arises and is there, and whoever is the first to express it does not create it, but merely dresses in words what is already unconsciously or half-consciously present in all hearts and brains.

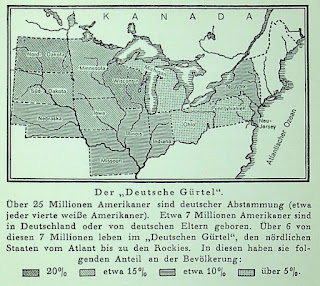

This idea, put in the shortest form, is: "Our America." Our America not only because German blood flows in at least twenty to thirty million Americans, not only because this blood has been liberally shed for the freedom as well as the unity of the Union, but because America is in its roots a creation of the German spirit, and because it can be brought over the grave crisis into which it has fallen today only if it finds its way back to these roots.

Such an assertion seems bold, and the conclusions drawn from it even bolder, at a time when the waves of German hatred are once again running high in the United States. But one hates only what one fears. From the beginning, the Anglo-Americans have feared and hated their ethnic Germans, each time they have become too numerous and too powerful for them. Fear and hatred were, of course, unnecessary; for the German-Americans have never used their power, much less abused it. Indeed, they probably never really became aware of it.

So the question is whether the millions who have been transplanted from German soil into American soil will recognize their hour of destiny, whether they will realize that this is a crucial moment when they must stand up and take upon themselves their share of responsibility for the future of the United States, not for Germany's sake, but for America's sake.

An Age is running out. A world turning point is lifting. No different in America than in the rest of the world. The questions which this change of shape and tide confronts each country, each people, cannot be solved by intellectual considerations, but only from the last depths of the blood and the heart. Only when the Americans of German blood become aware of what it means to be "Our America" - in rights, in duties, in ultimate responsibility - will they be able to give their new homeland, which is now their only one - for they have lost the old one - what it must demand of them, and what alone can redeem them from the curse of shuttling back and forth between two countries, two peoples, two cultures, two world views with torn hearts. "Our America", that means creating an America which is their homeland to the last, not in spite of, but because they are of German blood.

This America of the future can only arise from the past. The Americans of German blood must make their past, which has disappeared from them, their own again, not as an appendage to the history of the United States, but as a self-contained experience of destiny.

Comments

Post a Comment